О компании

Основатель фирмы

Ананов Андрей Георгиевич

Заслуженный деятель искусств России

Кавалер ордена Почета

1989 - Основана компания "Русское ювелирное искусство"

1991 - выставка в Лондоне

1991 - подписан контракт с парижской фирмой Elida-Gibbs Faberge о создании торговой марки "Фаберже от Ананова"

1991 - презентация коллекции фирмы в Париже в отеле "Риц"

1991 - вручение А.Г. Ананову международной премии "Серебряный лев" в Париже

1992 - открытие первого салона фирмы в Гранд Отеле "Европа" в Санкт-Петербурге

1992 - вручение А.Г. Ананову Большой золотой европейской медали в Генуе

1992 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Монако

1993 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Мадриде

1993 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Монако

1994 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Стокгольме

1995 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Париже

1995 - А.Г. Ананову присвоено почетное звание "Заслуженный деятель искусств России"

1996 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Сан-Пауло

1997 - А.Г. Ананов внесен в "Золотую Книгу" России

1998 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Москве

1999 - издан первый литературный труд А.Г. Ананова - книга "Два туза в прикупе"

1999 - открытие Главного салона фирмы на Невском проспекте,31, в историческом здании бывших "Серебряных рядов"

2000 - персональная выставка произведений фирмы в Оружейной палате московского Кремля

2000 - вручение А.Г. Ананову Ордена Карла Фаберже первой степени с бриллиантами и звания "Лучший ювелир столетия" на Международной выставке, посвященной 100-летию Всемирной выставки в Париже

2000 - выдвижение А.Г. Ананова на соискание Государственной премии России в области искусства и литературы

2001 - вручение А.Г. Ананову Царскосельской Премии

2003 - Награжден медалью «300 лет Санкт-Петербурга».

2004 - Награжден высшей наградой Общественного Совета - «Признательность Санкт-Петербурга»

2005 - Награжден Орденом Почета

2014 - выставка в Государственном Эрмитаже

2014 - Награжден Европейской золотой медалью за заслуги в профессиональной деятельности

2015 - выставка в Историческом музее в Москве

2016 - выставка на Международном экономическом форуме

Государственный Эрмитаж

Андрей Ананов - самый знаменитый ювелир России. Сверх того, он - социальное явление, символизирующее нашу жизнь последних десятилетий, почти литературный персонаж с историями театрального режиссерства, подпольной ювелирной работы, натиска молодого капиталиста и уверенности нового русского богатства.

Зачастую о нем говорят как об имитаторе или продолжателе Фаберже. К счастью, это не так. Он продолжает не Фаберже, а петербургский стиль в искусстве, частью которого стали и традиции Фаберже. Петербургский стиль родился тогда, когда архитекторы разных стран соединили свои национальные манеры в уникальный мир архитектуры Петербурга. А позднее петербургскому "серебряному веку" стало созвучно смешение разных исторических стилей в блеске причудливо-элегантной игры эмали с бриллиантами. Утонченная красота, которая сродни гниению и распаду, всегда была близка городу, чудом и волей построенному на болотах.

Этот стиль сегодня расцветает в руках Ананова и его мастеров, приобретая новые черты, не позволяющие, однако, забыть о предшественниках. Новые тенденции уводят пасхальные яйца дальше от их православного смысла, чем в начале века. В их сюжетах появляются мечети, полумесяцы и арабские надписи. Возможно, однако, что это - возвращение к универсальности символа жизни, рожденной жизнью.

Любимые архитектурные сюжеты Ананова сегодня - знаковые здания "московского" духа, храм Христа Спасителя и петербургский храм Воскресения Христова. Думаю, что и здесь нет стилистического предательства, а есть расширение границ стиля, завоевание новых территорий.

Прекрасные творения мастерской Ананова еще сулят нам много эстетических удовольствий, но и не меньше - бурных дискуссий. Остро спорить о судьбах прекрасного - тоже в традициях Петербурга, города, который дал России Ананова и украшению которого мастер отдает свои силы и талант.

Михаил Пиотровский

Директор Государственного Эрмитажа

Академик РАН,

Профессор

Как это начиналось

Ее Величество Елизавета II в Мариинском дворце.

А. Ананов преподносит английской королеве "Ветку ежевики".

Санкт-Петербург. 1994 год

Роскошная парадная лестница на углу Владимирского и Стремянной - со следами былой лепки, пустотами, оставшимися от некогда стоявших в аркадах статуй, засиженными мраморными подоконниками, пустыми винными бутылками, гранеными стаканчиками, аккуратно повешенными на кране батареи (символ всеобщего братства пъющих), лужей прокисшей мочи, сохранившей стойкий аромат портвейна "Агдам", обрывками использованных газет, обертками от плавленных сырков, колоритными надписями на стенах - являла собой как бы часть декорации жутковатого советского трагифарса.

На третьем этаже, нащупав в темноте разбитый выключатель, я заставил в последний раз улыбнуться пыльную электрическую лампочку, свисавшую на куске провода из того места, где некогда висела люстра. От люстр на лестничных площадках остались одни крючья, замершие как бы в ожидании логического завершения судеб завсегдатаев лестницы, хранивших до поры свой граненый стакан на трубе отопления.

Вспыхнувшая на мгновение лампочка тускло осветила истерзанную бесчисленным количеством звонков, табличек с причудливыми фамилиями, телевизионных кабелей, некогда роскошную деревянную резную дверь. Как кривая ухмылка из прошлого, на двери сохранилась медная табличка с хорошо различимой надписью: "Профессор Шустер. Венерические болезни".

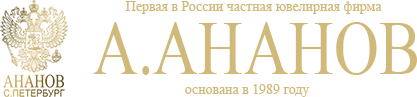

А. Ананов с дочерью Анной в день вручения

Большой золотой европейской медали.

Генуя. 1992 год

Мой приятель Юра, "артист Императорских театров", как он любил себя называть, занимал комнатку налево от входа, то ли бывшую людскую, то ли прозекторскую, длинную и темную, как слепая кишка.

В тот день выпить ему, как обычно, хотелось, а денег, как обычно, не было. И я был приглашен, а точнее, вызван по телефону как "скорая помощь", с инъекцией емкостью пол-литра в кармане.

По заплеванной лестнице вел меня Господь, привел в коммуналку и где-то после второго стакана указал в угол длинной Юриной комнатухи. Там между самодельным книжным стелажом - секретером, с вырезанным на крышке портретом хозяина, и аквариумом с дохлыми золотыми рыбками, стоял небольшой - специальный и необычный - заваленный инструментами рабочий стол

- Юра, что это?

Юра смутился и поежился. Видно было, что убрать инструменты и прикрыть стол, он не успел, вот и пришлось "колоться".

- Отец был ювелиром. Меня в детстве подучил. Я даже гравером работал. Ну балуюсь сейчас, колечки там, сережки в театре кое-кому ремонтирую... но ты не говори... сам знаешь, запрещенный промысел.

Во-первых, я этого, естественно, не знал, во-вторых, водка кончилась. А выпить мы тогда могли немало. В долг брать было не у кого, у всех и так уже было взято.

- Юра, какие проблемы! Ты же ювелир! Давай по- быстрому изготовь чего-нибудь, колечко там, я помогу, покручу или пополирую, и вперед!

- Да не в форме я сейчас... и вообще, куда это продавать... сомневаюсь я...

- Да ладно! Попитка не питка, как говорил товарищ Берия!

Мы сели рядом. Впервые я взял в руки хитроумный ювелирный инструмент, попилил надфилем кусочек настоящей серебряной проволоки, отполировал на волосяном круге, сбегал на угол, в ресторан "Москва", и вскоре появился с двумя бутылками водки и связкой сосисок...

С тех пор прошло двадцать пять лет...

В статье использованы главы из книги Андрея Ананова "Два туза в прикупе".

Несколько уроков ювелирного дела, полученных когда-то на улице Стремянной, не прошли даром. Тогда, двадцать пять лет назад, болел этой болезнью. Работая режиссером, переезжая из театра в театр, ставя драматические спектакли, я всегда возил за собой тяжелый чемодан с инструментами.

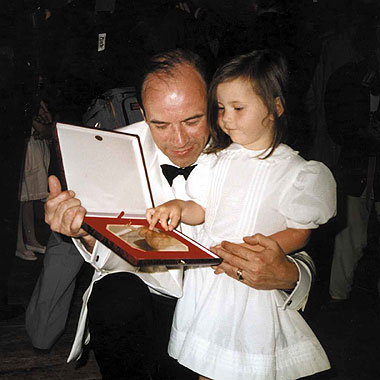

Мадам Ширак, супруга президента Франции,

на выставке произведений А. Ананова

Париж. 1995 год

К началу восьмидесятых годов я уже стал опытным ювелиром и работал дома, получая частные заказы. Моя душа разрывалась между любовью к своей театральной профессии и новым увлечением. После вечерней репетиции я сломя голову спешил домой и работал запоем, часто всю ночь, а утром снова бежал в театр.

Осенью восемьдесят первого в мою квартиру нагрянули с обыском из КГБ.

Как ни странно, но эта история решила мою судьбу. Я сделал выбор. И ушел из театра.

Семь лет я работал дома не разгибаясь, увлеченно и упрямо. Моя цель была грандиозна и нахальна. Я решил стать новым Фаберже, связать разорванную большевистской революцией ниточку, тянувшуюся из глубины времен, от великих русских ювелиров Шарфа и Позье, Раппопорта и Перхина... Я любил этот стиль, совершенный в манящем блеске тонко оправленных бриллиантов и зеркально отполированной эмали, напоминающий о безвозвратно ушедшей эпохе дворцов, светских приемов, мужественных подтянутых офицеров и изящных декольтированных дам, меня манила красивая иллюзия прошлого некогда богатой и могущественной державы.

Двух своих рук мне уже не хватало. Появились ученики, и часто маленькая пятнадцатиметровая квартирка, которую я в то время снимал и в которой умещался и мой рабочий стол, и токарный станок, и детская кроватка только что родившейся дочки Анюты, наполнялась теми, кого я учил премудростям уже постигнутого мной ремесла.

С детства я запомнил умную сказку про двух лягушат, попавших в подполе в крынку с молоком...

- Прощай, брат! - сказал один, сложил лапки и пошел на дно.

"Утонуть я всегда успею", - подумал другой. И барахтался до тех пор, пока, выбившись из сил, вдруг не почувствовал под собой опору и не выбрался: молоко превратилось в масло.

Мы барахтались, как могли, и сбили масло. Мы стали мастерами, и внезапно началась перестройка. Но это было лишь начало, только-только забрезжил свет в конце туннеля. Мне еще предстояло стать первым в России ювелиром, получить официальные права на изготовление изделий из золота и серебра.

Долгое время после начала перестройки крепко сколоченная советская система цеплялась за свои льготы и привилегии. Одной из привилегий и была государственная монополия на металл. А Комитетом по драгоценным металлам правили твердые указания руководства - "частников не пущать". И не пущали, тормозили изо всех сил. Постановлениями, проволочками, бюрократией и саботажем. Я разрубил этот узел. Я рискнул. Я привез коллекцию уникальных ювелирных предметов, сделанных своими руками, в Гохран и положил на стол тогдашнему председателю Комдрагмета Евгению Матвеевичу Бычкову. Изделия имели только одно клеймо - "Ананов", и отсутствие клейма Государственной пробирной инспекции являлось криминалом.

- Если вы - бюрократ и формалист, то снимайте телефонную трубку и вызывайте КГБ, - сказал я, - а если вы профессионал и вам не безразлична судьба русского ювелирного искусства - помогите мне получить право на изготовление этих изделий.

Бычков нахмурился, покраснел и взялся за лупу. Время потянулось мучительно... Наконец он закончил осмотр и снял трубку правительственного телефона. Я замер.

Бычков оказался профессионалом, и ему, и его другу, начальнику Государственной пробирной инспекции России Валентину Никитину, была небезразлична судьба ювелирного искусства России.

Я первый получил лицензию на изготовление изделий из золота. Мандат номер один.

Так рухнула советская монополия на драгоценные металлы, и разрушил ее я. А вслед за мной пошли другие. Им было уже проще - я шел впереди и рассекал ветер.

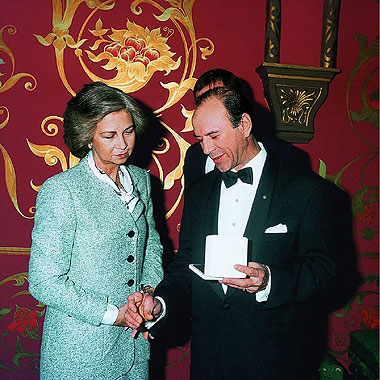

Ее Величество королева Испании София

на выставке произведений А. Ананова.

Мадрид. 1993 год

Мир не без добрых людей. Мне удалось после длительных хождений по инстанциям зарегистрировать кооператив и получить в аренду помещение под мастерскую. Туда и пришли те, с кого она начиналась. Первые, кто мне поверил. Вот их имена: Владимир Ратушев, Виталий Харламов, Виктор Муров, Юрий Бабков. Несколько позже - Владимир Ковалев, Вячеслав Леонов, Михаил Навроцкий, Валерий Линский, Андрей Шевченко, Вадим Гусев. Уникальный механик Павел Смолкин.

Мы сидели рядом, за верстаками, сколоченными собственными руками из старых канцелярских столов, найденных на свалке. У нас не было денег, из щелей дуло, под полом жили крысы.

А я мечтал вслух о том времени, когда мы объедем полмира, показывая наши изделия на выставках, и станем первыми и лучшими. И будем хорошо жить, и ездить отдыхать за границу.

Я умею убеждать. Я научился этому искусству, работая режиссером, и перенес этот навык в мастерскую. И пусть не сразу, но мои коллеги мне поверили.

Только теперь я могу признаться, что сам поверил в эти радужные перспективы последним. Убеждал других, вселял в людей оптимизм, в то же время - не верил в реальность осуществления своих грандиозных планов. Но никогда не показал этого. И передал коллективу свою уверенность.

И мы сделали это.

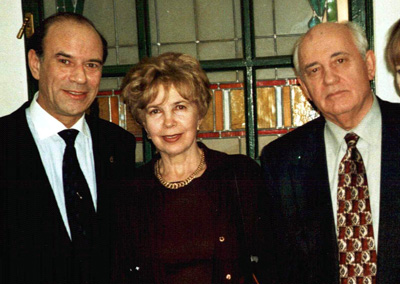

Горбачев с Раисой Максимовной

Наши взаимоотношения строились на принципах доверия и уважения. Я не проверял карманы своих мастеров. Я ликвидировал понятие "угар" золота, понятие, которое неизбежно приводит к воровству на ювелирных производствах, потому что как бы честно ни отчитывался работник за драгметалл перед начальством, у него всегда скопится несколько граммов золота за месяц. И что потом с ним делать? Вручить хозяину?.. Я не идеалист. Я знаю, что соблазн велик и золото превратится в слиток или "левое" изделие или "утечет" из мастерской. Теперь "угар" как бы не существовал, и мастер работал из полученного кладовой металла до тех пор, пока не перерабатывал его в изделия и не получал в кладовой новую порцию.

Во дворце Гримальди: принц Альберт внимательно осматривает произведение А.Ананова. Утром Монте-Карло узнает о сенсации - пасхальное яйцо из России станет Главным призом Бала Красного Креста, отодвинув на вторую позицию бриллиантовое колье, изготовленное фирмой Картье. 1994

Я создал в фирме условия, когда главным требованием стало любить свою профессию и следовать канонам старых мастеров, говоривших: лицевая сторона изделия, естественно, красива, нo качество мастера не в ней. Оно - на обратной стороне. И по тому, как тщательно и совершенно выглядит "изнанка" изделия, можно судить о мастерстве ювелира.

С дочерьми Анной и Анастасией, 2004 г.

И еще. Я никогда не обманывал своих коллег. Нe скрывал от них собственный горький опыт алкоголизма, от которого меня спасли моя любовь к ювелирному труду и моя дочка Анюта, я не скрывал цены, по которым продавал изделия клиентам, я не скрывал свою позицию в жизни, взгляды, правила своего поведения. Это касалось и повседневности, и переломных моментов в беспокойной истории нашего Отечества.

Ее Величество Королева Тайланда в мастерской А.Ананова во время официального визита в Россию в августе 2007 года

Вот уже более двадцати пяти лет существует мастерская. Один за другим к нам приходили новые люди. Главным критерием при отборе была любовь к избранной профессии. Большинство ювелиров, научившихся здесь высотам мастерства, раньше были инженерами, врачами, военнослужащими, но всех их объединяло одно - у себя на кухне, в свободное время, они что-то мастерили своими руками.

Король и Королева Малайзии

Однажды в Монте-Карло на выигранные в рулетку деньги я купил свой первый "Мерседес". Это был реванш за конный завод, проигранный когда-то там же, в Монте-Карло, моим дедом. А ювелирное искусство, проигранное Россией в семнадцатом году? Думаю, что отыграл и его, возродив в стране высокие ювелирные традиции прошлых лет. И это - второй реванш.

С дочерью Ольгой, 2015г.

Я мог, по совету друзей-матросов, стать профессиональным моряком.

Я мог доучиться в университете и работать физиком.

Я, режиссер по образованию, мог ставить спектакли и учить студентов в Театральном институте.

Я мог, в конце концов, спиться, покончить с собой, сгинуть, как сгинули многие талантливые люди моего поколения.

Но мне повезло. Я выжил, Я нашел свой путь и сумел изобрести формулу бессмертия, лаконичное послание в вечность: несколько граммов золота, немного эмали, чуть-чуть бриллиантов, частица души и ветерок вдохновения. И на всем этом - русское клеймо "Ананов".